Understanding Deer Dietary Habits

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and other deer species are known for their adaptable feeding patterns, consuming a wide variety of vegetation throughout the changing seasons. As herbivores, deer primarily feed on leaves, twigs, grasses, agricultural crops, fruits, nuts, and occasionally fungi. Their dietary preferences shift based on seasonal availability, nutritional needs, and environmental conditions.

For mushroom hunters and wildlife enthusiasts alike, the question "do deer eat morel mushrooms?" represents an intriguing intersection of wild foraging interests. Understanding deer dietary habits in relation to these prized fungi can provide insights for both morel hunters and those interested in deer behavior and ecology.

This comprehensive guide explores the relationship between deer and morel mushrooms, examining evidence of consumption, factors affecting deer feeding behavior, and the ecological implications of their foraging habits.

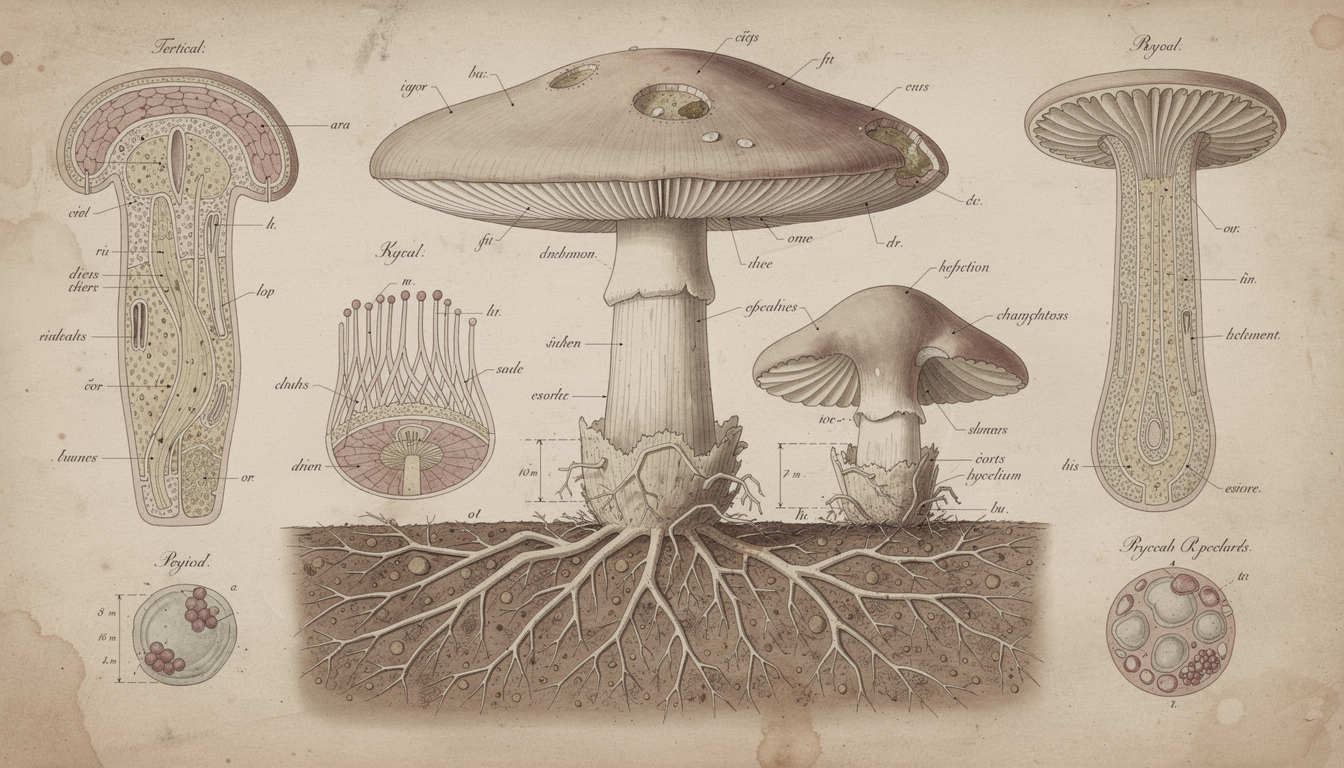

Deer and Fungi: General Relationship

Fungi in Deer Diets

While deer are primarily browsers of woody and herbaceous plants, research has documented their consumption of various fungi:

- Seasonal consumption: Fungi may constitute a small but notable portion of deer diets, particularly in late spring and fall

- Nutritional factors: Some fungi provide protein, minerals, and other nutrients that complement plant-based diets

- Opportunistic feeding: Deer typically consume fungi when encountered during regular browsing

- Regional variations: Consumption patterns vary based on habitat type and fungal abundance

- Species preferences: Deer may show preference for certain fungal species over others

These general patterns provide context for examining morel-specific consumption.

Documented Fungi Consumption

Scientific studies and field observations have recorded deer eating several types of fungi:

- Truffles and false truffles: Underground fungi that deer may dig up

- Puffballs: Large, round fungi that appear in meadows and forests

- Bracket fungi: Shelf-like growths on trees, occasionally browsed by deer

- Various mushrooms: Including certain gilled mushrooms when available

- Mycorrhizal fungi: Associated with tree roots and often consumed by deer in forest settings

This documented fungal consumption suggests the possibility of morel consumption as well.

Evidence of Deer Eating Morel Mushrooms

Direct Observations

Field evidence regarding deer consumption of morel mushrooms:

- Hunter observations: Numerous morel hunters report finding partially eaten morels with bite patterns consistent with deer

- Wildlife camera documentation: Some trail camera footage has captured deer investigating and consuming morels

- Tracking evidence: Deer tracks and signs found around disturbed morel patches

- Behavioral observations: Wildlife biologists have occasionally documented deer browsing in areas with emergent morels

- Stomach content analysis: Limited scientific studies examining deer stomach contents have found morel fragments, though such research is relatively sparse

These observations provide compelling, if anecdotal, evidence that deer do indeed consume morels.

Circumstantial Evidence

Additional indicators suggesting deer consumption:

- Disappearing patches: Morel hunters commonly report finding an area with small, emerging morels only to return days later to find them missing, with deer tracks nearby

- Bite patterns: Characteristic bite marks on remaining mushroom portions match deer dentition

- Browsing height: Morels at deer browsing height (up to about 6 feet) disappear more frequently than those in less accessible locations

- Seasonal overlap: The spring morel season coincides with a period when deer are actively seeking nutrient-rich food after winter

- Habitat sharing: Deer and morels often inhabit the same ecological niches, particularly around disturbed forest areas and edge habitats

While not definitive proof, these patterns strongly suggest deer consumption of morels.

Factors Affecting Deer Consumption of Morels

Seasonal Timing

How seasonal factors influence potential morel consumption:

- Spring emergence: Morels typically appear in spring when deer are recovering from winter nutritional stress

- Dietary transition period: Spring represents a transition from winter woody browse to fresh growth

- Nutritional needs: Female deer have increased nutritional demands during pregnancy in spring

- Antler growth: Male deer begin antler development in spring, requiring calcium and other minerals

- Alternative food availability: Consumption may depend on availability of preferred vegetation

These seasonal factors potentially make morels an attractive food source during their fruiting period.

Habitat Overlap

Shared habitat characteristics between deer and morels:

- Forest edges: Both morels and deer frequently utilize forest edge environments

- Disturbed areas: Recent burns, logging sites, and other disturbed areas attract both deer and promote morel growth

- Tree associations: Morels often grow near trees that deer browse, such as ash, elm, and apple

- Soil conditions: Rich, moist soils that support morel growth often produce vegetation deer prefer

- Sunlight patterns: Dappled light areas favorable to morels also attract deer for browsing

This habitat overlap increases the likelihood of deer encountering morels during foraging.

Nutritional Value

Potential nutritional benefits morels offer to deer:

- Protein content: Morels contain approximately 3g protein per 100g, supplementing deer's spring diet

- Mineral composition: Rich in potassium, copper, and zinc—minerals beneficial for antler growth

- Vitamin D presence: Morels exposed to sunlight develop vitamin D, potentially beneficial to deer

- Low toxicity: Properly matured morels present minimal toxicity concerns for deer

- Water content: High moisture content may be attractive during dry spring periods

These nutritional factors might make morels an attractive supplemental food source.

Competing Wildlife for Morel Consumption

Other Mushroom-Eating Animals

Deer aren't the only wildlife consuming morels:

- Squirrels: Gray and red squirrels are known morel consumers

- Chipmunks: Frequently observed eating and collecting morels

- Wild turkeys: Often scratch for and consume morels and other fungi

- Box turtles: Documented consuming morels they encounter

- Various rodents: Mice, voles, and other small mammals eat morels opportunistically

This competition may affect both the availability of morels and deer foraging behavior.

Determination Through Evidence

Distinguishing deer consumption from other wildlife:

- Bite height: Deer typically browse at heights of 2-6 feet above ground

- Bite pattern: Deer leave jagged, torn edges rather than the clean cuts of rodent teeth

- Track evidence: Deer leave distinctive hoof prints around feeding sites

- Browse pattern: Deer often consume multiple morels in an area, while smaller animals may focus on single specimens

- Remaining material: Deer typically leave the stem base while consuming the cap, unlike some smaller animals that take entire mushrooms

These characteristics help morel hunters identify deer as the likely consumers of missing or partially eaten morels.

Implications for Morel Hunters

Competition With Wildlife

How deer consumption impacts morel hunting:

- Early harvesting importance: Finding morels before deer do can significantly affect harvest success

- Peak timing considerations: Understanding when deer are most likely feeding can influence hunting schedules

- Location strategy: Areas with heavy deer traffic may have fewer remaining morels

- Height awareness: Checking obscured locations where deer are less likely to browse

- Population density effects: Areas with high deer populations may experience greater morel predation

These factors can help morel hunters adjust their strategies to maximize success.

Trail Camera Evidence

Using wildlife monitoring to improve morel hunting:

- Strategic placement: Setting trail cameras in known morel-producing areas

- Timing insights: Cameras can reveal when deer are most active in morel habitats

- Behavior patterns: Understanding deer browsing patterns around morel patches

- Confirmatory evidence: Documenting actual consumption behavior

- Predictive value: Using deer activity to predict morel emergence in similar habitats

This technology bridge between wildlife observation and mushroom hunting provides valuable data.

Hunting Pressure Correlation

Relationship between deer hunting and morel availability:

- Population management: Areas with controlled deer populations may have more available morels

- Post-hunting season effects: Fall hunting pressure may influence spring deer distribution and feeding patterns

- Property access overlap: Private lands that permit deer hunting may have less deer pressure on morel populations

- Conservation land management: Wildlife management practices affect both deer populations and morel habitat

- Ecological balance: Proper deer management helps maintain ecosystem services that support morel production

This relationship highlights the interconnected nature of wildlife management and non-timber forest resources.

Ecological Significance of Deer-Morel Interactions

Spore Dispersal Role

How deer may contribute to morel propagation:

- Digestive survival: Some fungal spores survive passage through deer digestive systems

- Movement patterns: Deer typically travel several miles daily, potentially spreading spores

- Habitat connections: Deer movement between forest patches may establish new morel colonies

- Deposition conditions: Deer scat provides nutrient-rich environment for spore germination

- Research limitations: Limited scientific research specifically addressing deer-assisted morel dispersal

While not conclusively proven, the potential role of deer in spore dispersal represents an intriguing ecological question.

Ecosystem Functions

Broader ecological context of deer-fungi relationships:

- Forest succession influence: Deer browsing patterns affect forest composition, indirectly impacting morel habitat

- Soil ecology: Deer contribute to nutrient cycling that may benefit fungal communities

- Disturbance regimes: Deer create small-scale soil disturbances that might benefit certain fungi

- Trophic interactions: Deer serve as links between plant and fungal communities in forest ecosystems

- Biodiversity relationships: Moderate deer populations can maintain diverse habitats favorable to morels

These ecological relationships illustrate how deer influence the environments where morels thrive.

Conservation Implications

Management considerations regarding deer and morel resources:

- Overabundance concerns: Excessive deer populations can negatively impact forest understory diversity, potentially affecting morel habitat

- Balanced management: Maintaining deer populations at ecologically appropriate levels benefits overall forest health

- Habitat protection: Preserving diverse forest habitats supports both deer and morel populations

- Sustainable harvest: Both deer and morels represent renewable resources when properly managed

- Research needs: More study needed on non-game wildlife impacts on non-timber forest products

These conservation perspectives highlight the importance of integrated natural resource management.

Research on Deer Dietary Preferences

Scientific Studies

Academic research relevant to deer-morel interactions:

- Rumen content analysis: Studies examining stomach contents of deer have occasionally found fungal material

- Feeding preference trials: Controlled studies show deer will consume certain mushroom species when offered

- Nutritional analysis research: Work on deer nutritional needs during spring coincides with morel availability

- Behavioral ecology studies: Research on deer foraging patterns provides context for potential morel consumption

- Regional variations: Studies from different geographic areas show varying levels of fungi consumption

While specific research on deer-morel relationships remains limited, these broader studies provide relevant context.

Limitations in Current Knowledge

Gaps in scientific understanding:

- Limited direct research: Few studies specifically address deer consumption of morels

- Observational bias: Most evidence comes from human observations rather than controlled studies

- Seasonal sampling challenges: Short morel season makes systematic study difficult

- Regional variations: Deer behavior varies significantly across geographic regions

- Species differences: Different deer species may have varying propensities for mushroom consumption

These knowledge gaps present opportunities for further research and citizen science.

Practical Strategies for Morel Hunters

Timing Considerations

Optimizing morel hunting relative to deer activity:

- Early season focus: Hunt early in the season before deer discover emerging morels

- Daily timing: Consider hunting during periods of lower deer activity (mid-day)

- Weather patterns: Deer movement decreases during certain weather conditions

- Post-rain strategy: Check sites shortly after rainfall when new morels emerge

- Seasonal progression: Follow the morel season to higher elevations or northern areas as the season advances

Strategic timing can help hunters find morels before deer consume them.

Location Selection

Choosing locations with potentially lower deer pressure:

- Steeper slopes: Deer tend to browse less frequently on steep terrain

- Dense understory: Areas with thick brush may deter deer while still supporting morels

- Human activity zones: Areas with regular human presence may have less deer activity

- Fenced areas: Check inside fenced portions of forests where deer access is limited

- Alternative habitat types: Explore morel habitats less frequently utilized by deer

These location strategies may increase success in finding intact morels.

Protection Methods

For those growing or managing morel areas:

- Physical barriers: Small fencing or netting around known morel patches

- Repellent options: Commercial or homemade deer repellents may deter browsing

- Companion planting: Growing deer-repellent plants near morel habitat

- Disturbance techniques: Regular human presence can discourage deer activity

- Hunting management: Appropriate deer population control in hunting seasons

These protection methods may be relevant for landowners managing morel production areas.

Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge

Historical Perspectives

Traditional knowledge regarding deer and morels:

- Indigenous observations: Many Native American tribes recognized the relationship between deer and certain fungi

- Traditional ecological knowledge: Historical understanding of wildlife feeding patterns informed foraging practices

- Seasonal indicators: Deer behavior was traditionally used as an indicator for mushroom hunting timing

- Ethical harvesting: Cultural practices often emphasized leaving some mushrooms for wildlife and regeneration

- Complementary harvesting: Traditional hunters often noticed mushroom presence while tracking deer

This historical knowledge often predates and complements scientific understanding.

Cultural Significance

The cultural context of deer-morel relationships:

- Spring renewal symbolism: Both deer activity and morel emergence signify spring renewal in many cultures

- Subsistence perspectives: Traditional communities valued understanding the relationship between wildlife and gathered foods

- Knowledge transmission: Information about wildlife-mushroom interactions passed through generations

- Holistic ecological view: Traditional knowledge typically recognized interconnections between species

- Seasonal celebrations: Spring mushroom abundance and wildlife activity featured in cultural celebrations

These cultural dimensions add depth to the ecological understanding of deer-morel interactions.

Conclusion: The Complex Relationship Between Deer and Morels

The question "do deer eat morel mushrooms?" can be answered with a qualified yes—substantial evidence indicates that deer do indeed consume morels when they encounter them. This relationship represents just one facet of the complex ecological web connecting wildlife, fungi, and forest ecosystems.

For morel hunters, understanding deer behavior and foraging patterns can provide practical advantages when searching for these elusive mushrooms. Recognizing deer sign, understanding their movement patterns, and timing hunts accordingly may improve success rates.

From an ecological perspective, deer consumption of morels may serve important functions in spore dispersal and nutrient cycling, though more research is needed to fully understand these relationships. The interaction between deer and morels reminds us that forest ecosystems operate as integrated wholes, with each species playing multiple ecological roles.

Whether you're a dedicated morel hunter, a wildlife enthusiast, or simply curious about forest ecology, the relationship between deer and morels offers a fascinating glimpse into the interconnected nature of woodland communities and the many ways species interact in shared environments.

Share:

Wild Morel Mushrooms: A Forager’s Delight and Nature’s Hidden Treasure

How to Grow Morel Mushrooms at Home Easily