Have you ever looked at a mushroom and wondered what all those different parts actually do? Understanding mushroom anatomy transforms how you view these fascinating organisms and dramatically improves your success as a home cultivator. Whether you're growing oyster or lion's mane mushrooms at home or simply curious about fungal biology, knowing how mushrooms work helps you provide the perfect growing conditions for maximum yields.

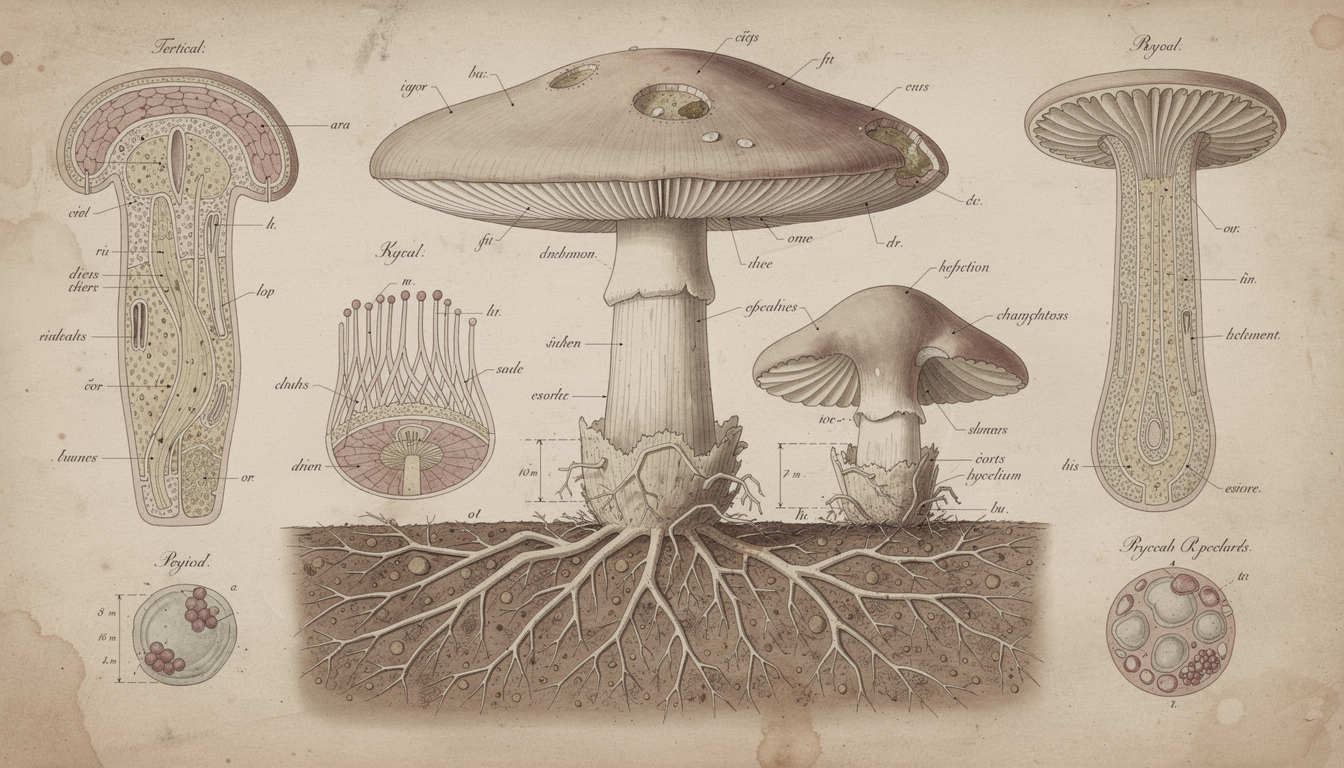

Mushroom anatomy is far more complex than the simple "cap and stem" description most people know. From the visible fruiting body above ground to the massive mycelial networks hidden underground, every part of a mushroom serves critical functions in the organism's life cycle. This comprehensive guide explores mushroom anatomy from the microscopic level to full fruiting bodies, explaining how each component works together to create the mushrooms we harvest and enjoy.

The Visible Mushroom: Understanding Fruiting Body Structure

When most people think of mushrooms, they picture the fruiting body—the reproductive structure that emerges above ground or from growing substrates. However, this visible portion represents just a small fraction of the complete organism, analogous to an apple on an apple tree rather than the entire tree itself.

The fruiting body develops specifically for reproduction, concentrating tremendous energy into creating, protecting, and dispersing millions or even billions of spores. Understanding each component of the fruiting body helps cultivators recognize when mushrooms have reached optimal harvest timing while identifying potential problems during development.

A mushroom fruiting body typically develops from a nodule called a primordium, less than two millimeters in diameter, found on or near the substrate surface. This tiny structure rapidly inflates with water and expands into the familiar mushroom shape we recognize. The speed of this transformation explains why mushrooms seem to appear overnight after rain or when conditions suddenly become optimal.

For those growing mushrooms at home, the Lykyn Smart Mushroom Grow Kit provides the precise environmental conditions needed for healthy fruiting body development. The system's automated humidity and airflow controls ensure proper formation of all anatomical structures, resulting in well-formed mushrooms with fully developed caps, properly structured gills, and firm stems.

The Mushroom Cap (Pileus): Nature's Protective Umbrella

The cap represents the most recognizable feature of mushroom anatomy. This umbrella-like structure serves multiple critical functions that ensure successful reproduction and species survival. The cap protects the delicate gill tissue underneath from direct sunlight, wind, and rain that could damage spore-producing surfaces or wash spores away before they disperse properly.

Cap size, shape, color, and texture vary dramatically across mushroom species, providing key identification characteristics for foragers and cultivators. Button mushrooms feature smooth, round caps that flatten as they mature. Oyster mushrooms develop shelf-like caps in shades of white, gray, pink, or golden yellow. Lion's mane mushrooms create cascading tooth-like structures rather than traditional caps, demonstrating the remarkable diversity of fruiting body architecture.

The cap's underside houses the hymenium—the spore-bearing tissue that represents the mushroom's primary reproductive machinery. Cap expansion timing signals harvest readiness for many species. Oyster mushrooms reach peak quality when caps fully expand but edges haven't yet curled upward. Shiitake mushrooms develop best flavor and texture when caps open fully but the protective veil underneath remains mostly intact.

Environmental conditions during fruiting significantly affect cap development. Insufficient humidity causes caps to crack and develop irregularly. Poor fresh air exchange results in small, underdeveloped caps with elongated stems. The sophisticated sensors in automated growing systems monitor these conditions continuously, adjusting humidity and airflow to promote ideal cap formation throughout development.

Gills, Pores, and Spore-Producing Surfaces

Underneath the protective cap lies the hymenium—specialized tissue responsible for producing and releasing spores. The structure of this tissue varies significantly across mushroom families, creating distinct anatomical differences that help identify species and understand their evolutionary relationships.

Gilled mushrooms (like oyster, shiitake, and button varieties) feature thin, blade-like structures radiating outward from the stem to the cap edge. These gills provide massive surface area for spore production within a compact space. Each gill is lined with millions of microscopic cells called basidia (in Basidiomycete mushrooms) that produce spores through sexual reproduction.

The spacing, attachment pattern, and color of gills provide crucial identification markers. Free gills don't connect to the stem, while attached gills join the stem at various points. Gill color often changes as mushrooms mature and begin releasing spores—white gills may darken to pink, brown, or black depending on spore color. Understanding these changes helps cultivators time harvests for optimal quality and prevents excessive spore release that creates mess in growing areas.

Polypore mushrooms (like reishi and turkey tail) feature pores instead of gills. These tiny openings on the cap's underside lead to tube-like structures where spores develop and release. The pore structure provides similar surface area to gills while creating different spore dispersal patterns and protecting spore-producing tissue from environmental exposure.

Toothed mushrooms (like lion's mane and hedgehog mushrooms) produce spores on tooth-like or spine-like projections hanging from the fruiting body. These unique anatomical structures create distinctive appearances while serving the same fundamental reproductive function as gills and pores.

The Mushroom Stem (Stipe): Support and Transport System

The stem provides structural support that positions the cap at optimal height for spore dispersal. Like plant stems, mushroom stems transport water and nutrients from the mycelium to developing fruiting bodies. However, unlike plant vascular systems, fungal transport occurs through simpler mechanisms involving water pressure and diffusion through hyphal networks.

Stem characteristics vary significantly by species and growing conditions. Some mushrooms develop central stems that attach to the cap's center, while others feature off-center or lateral attachment. Oyster mushrooms growing on vertical surfaces often develop minimal stems, while those fruiting from horizontal substrates form more pronounced stems. This adaptability demonstrates how mushroom anatomy responds to environmental pressures.

Stem length and thickness indicate growing conditions during development. Mushrooms grown in high carbon dioxide environments develop elongated, thin stems with small caps—a condition called "legging" or "trumpeting." This anatomical distortion signals inadequate fresh air exchange. Proper ventilation produces shorter, thicker stems with well-proportioned caps that deliver better texture and culinary quality.

The stem's interior structure consists of packed hyphae aligned vertically to maximize strength and transport efficiency. Some species develop hollow stems as they mature, while others maintain solid interiors throughout their life cycle. Understanding these patterns helps cultivators distinguish between normal development and problematic conditions that might indicate contamination or disease.

Additional Fruiting Body Structures

Several mushroom species develop additional anatomical features that protect developing fruiting bodies or assist in spore dispersal. The ring (annulus) appears as a collar or skirt around the stem, representing the remnants of a protective membrane that covered immature gills. This partial veil protects developing gills until the cap expands, then tears to create the characteristic ring structure visible on mature mushrooms like portobello and certain Amanita species.

The volva forms a cup-like structure at the stem base in some species, representing remnants of the universal veil that completely enclosed the immature mushroom. This feature provides critical identification information, particularly for distinguishing between edible and potentially deadly species in the Amanita family. Foragers must carefully examine the stem base by digging around it rather than cutting at ground level to observe whether a volva is present.

Not all mushroom species develop these additional structures. Many popular culinary and medicinal varieties feature simple anatomy with just cap, gills or pores, and stem. The presence or absence of rings and volvas reflects evolutionary adaptations to different environmental conditions and dispersal strategies rather than indicating superior or inferior species.

The Hidden Network: Mycelium and Hyphal Structure

While the fruiting body captures attention with its rapid growth and familiar form, the mycelium represents the true body of the fungal organism. This vast underground network of thread-like structures called hyphae can extend through cubic meters of soil or substrate, far exceeding the size of any individual mushroom it produces.

Mycelium functions analogously to plant root systems, though the comparison only goes so far. Like roots, mycelium anchors the organism, absorbs water and nutrients, and supports fruiting body development. However, mycelium also secretes powerful digestive enzymes that break down complex organic compounds external to the organism—something plant roots cannot do.

Individual hyphae measure just a few micrometers in diameter, visible only under microscopes. However, these microscopic threads organize into visible networks recognizable as white, fuzzy growth spreading through substrates. When you purchase mushroom fruiting blocks, the solid white appearance throughout the substrate indicates complete mycelial colonization ready for fruiting.

Each hypha grows from its tip through a process called apical growth, allowing the organism to explore its environment efficiently. Hyphae branch repeatedly, creating increasingly complex networks that maximize surface area contact with food sources. This growth pattern enables fungi to locate and exploit nutrient-rich zones while avoiding less favorable areas within their substrate.

Hyphal Structure and Function

Fungal hyphae possess unique cellular organization that distinguishes them from both plant and animal cells. While sharing eukaryotic characteristics like membrane-bound nuclei with plants and animals, fungi feature cell walls made of chitin rather than cellulose (plants) or no cell walls (animals). Chitin—the same material found in insect exoskeletons—provides structural strength while maintaining flexibility.

Many fungi develop septate hyphae, where individual hyphal cells separate through cross-walls called septa. These septa contain pores allowing cytoplasm, nutrients, and even organelles to flow between cells, creating a semi-continuous internal environment. This organization enables rapid resource redistribution throughout the mycelial network, supporting explosive fruiting body growth when conditions become favorable.

Some fungi produce coenocytic hyphae without septa, creating long tubes containing multiple nuclei sharing continuous cytoplasm. This anatomical variation reflects different evolutionary strategies, with coenocytic forms typically growing and colonizing substrates faster than septate species.

The mycelial network demonstrates remarkable intelligence despite lacking a brain or nervous system. Mycelium can sense and respond to environmental gradients, directing growth toward food sources and away from toxins. The network can "remember" previous stimuli and adjust future responses accordingly. Research has even demonstrated that mycelium can solve maze problems and optimize network efficiency in ways similar to human-designed transportation systems.

Specialized Hyphal Structures

Beyond basic vegetative hyphae, fungi develop specialized structures for specific functions. Rhizomorphs are thick, root-like bundles of hyphae that transport nutrients over longer distances and help fungi colonize new territories. These structures appear as cord-like threads, sometimes visible to the naked eye, extending through soil or along decaying wood.

Clamp connections appear as small bulges on septate hyphae in many Basidiomycete species, ensuring proper nuclear distribution during cell division. While these microscopic structures seem like minor details, their presence or absence helps mycologists identify species and understand evolutionary relationships between different fungi.

Appressoria are specialized penetration structures that some fungi develop when they encounter resistant surfaces. These structures generate tremendous pressure—sometimes exceeding that of car tires—to physically puncture host tissues. While most cultivated mushroom species don't produce appressoria (they grow on pre-prepared substrates), understanding this anatomy helps explain how certain species colonize living wood or persist in challenging environments.

Mushroom Reproduction: Spores and the Life Cycle

Understanding reproductive anatomy completes the picture of how mushrooms function as organisms. While the visible fruiting body receives attention, the microscopic spores it produces drive the entire life cycle and ensure species survival across generations.

Mushrooms produce astronomical numbers of spores—a single large mushroom can release billions of microscopic reproductive cells. These spores develop within specialized cells on gill, pore, or tooth surfaces depending on species anatomy. In Basidiomycete mushrooms (the majority of culinary varieties), cells called basidia each produce four spores on external projections called sterigmata.

Spores are significantly simpler structures than plant seeds. A spore contains genetic material and minimal stored energy, requiring immediate access to nutrients upon germination. This simplicity allows mushrooms to produce spores in quantities that would be impossible with seed-like structures. The strategy relies on overwhelming numbers to ensure some spores land in favorable locations despite the low success rate of any individual spore.

Spore color, size, shape, and surface texture provide crucial identification characteristics for species differentiation. Mycologists create spore prints by placing mushroom caps gill-side-down on paper or glass, allowing spores to drop and accumulate. The resulting pattern and color help identify species—white spores indicate one group of mushrooms, while brown, black, or pink spores suggest different taxonomic groups.

For home cultivators interested in advanced techniques, collecting spores enables propagation of favorite varieties. Our guide on how to grow mushrooms from spores explains detailed methods for spore collection, germination, and cultivation from these microscopic starting points. While more challenging than using prepared fruiting blocks, spore cultivation provides complete control over genetics and strain selection.

From Spore to Mushroom: The Complete Cycle

The mushroom life cycle begins when spores land in suitable environments with adequate moisture, appropriate temperature, and available nutrients. Under favorable conditions, spores germinate, producing thin hyphal threads that begin exploring their surroundings. This initial growth remains invisible to the naked eye, occurring at microscopic scales.

When compatible hyphae from different spores meet, they fuse in a process called anastomosis. This fusion creates dikaryotic mycelium containing two distinct nuclei in each cell—think of this as roughly equivalent to the combination of genetic material that occurs during sexual reproduction in animals. The dikaryotic mycelium represents the dominant life stage for most mushroom species, potentially persisting for years while vegetatively colonizing substrates.

Environmental triggers including temperature changes, humidity increases, light exposure, or substrate nutrient depletion signal the mycelium to transition from vegetative growth to reproduction. The organism begins accumulating resources and organizing hyphal tissue into primordial knots—the first visible signs of developing fruiting bodies. These tiny nodules rapidly expand into recognizable mushroom pins, then mature into full-sized fruiting bodies.

The mature mushroom releases spores, completing the cycle. Understanding this progression helps cultivators provide appropriate conditions at each developmental stage. Learn more about these stages in our comprehensive guide to mushroom fruiting body development, which explains optimal conditions for each phase from pinning through harvest.

How Mushroom Anatomy Affects Growing Success

Understanding mushroom anatomy directly translates into better growing results. Each anatomical structure provides visual indicators of growing conditions, allowing cultivators to diagnose problems and adjust environments for optimal development.

Elongated stems with small caps indicate insufficient fresh air exchange, as discussed earlier. The mushroom anatomy adjusts to high CO₂ environments by prioritizing stem height to position caps above stagnant air layers in natural settings. In cultivation, this signals the need for increased ventilation. The Lykyn Smart Mushroom Grow Kit prevents this issue through variable-speed intake and outtake fans that maintain ideal CO₂ levels automatically.

Cracked or irregular caps result from inadequate humidity during development. As primordia expand rapidly, they require tremendous water uptake—remember that mushrooms consist of approximately 90% water. Insufficient environmental humidity prevents proper cap expansion, creating deformities visible in the final mushroom anatomy. Automated humidity systems maintain consistent conditions that support normal anatomical development without daily manual intervention.

Pale coloration or reduced pigmentation often indicates inadequate light exposure. While mushrooms don't photosynthesize, light serves as an environmental signal that influences various aspects of fruiting body anatomy including cap pigmentation, stem length, and gill development. Our article on mushroom light requirements explains optimal lighting for different species and growing situations.

Premature spore release, indicated by dark spore deposits around mushrooms, suggests overripe harvests. While this doesn't harm the mushrooms' edibility, it creates mess and slightly diminishes flavor. Understanding the anatomical indicators of maturity—cap expansion, veil breakage, gill darkening—enables cultivators to time harvests for peak quality before excessive sporulation occurs.

Comparing Mushroom Anatomy Across Popular Species

Different mushroom species exhibit fascinating anatomical variations that reflect their evolutionary adaptations and ecological roles. Understanding these differences helps cultivators provide species-specific growing conditions while appreciating the remarkable diversity within the fungal kingdom.

Oyster mushrooms develop shelf-like fruiting bodies with off-center or lateral stems when growing on vertical surfaces like tree trunks. This anatomy maximizes spore dispersal from vertical substrates. The gills run down onto the stem (decurrent attachment), creating efficient spore-launching surfaces. Cap colors range from white through gray, pink, golden, and blue depending on species, with all variants producing similar anatomical structures adapted for their ecological niche.

Shiitake mushrooms feature more traditional central-stemmed anatomy with convex caps that flatten with age. The gills attach to the stem in various patterns depending on strain. Shiitake caps develop characteristic cracking patterns that create decorative appearances valued in culinary presentations. Understanding these normal anatomical features prevents mistaking natural patterns for contamination or disease.

Lion's mane mushrooms display unique anatomy completely different from typical cap-and-stem structures. These mushrooms develop as masses of cascading tooth-like spines hanging from a central attachment point. Spores form on the external surfaces of these teeth rather than on protected gill surfaces. This distinctive anatomy requires slightly different growing approaches explained in our lion's mane cultivation guide.

Button, cremini, and portobello mushrooms represent different maturity stages of the same species (Agaricus bisporus) with identical basic anatomy. Buttons are harvested young with closed caps and white gills. Cremini mushrooms are slightly more mature with brown caps. Portobellos are fully mature specimens with caps opened flat and dark gills exposed. This progression demonstrates how mushroom anatomy changes throughout the fruiting body's development.

Mushroom Anatomy and Nutritional Content

The anatomical components of mushrooms contribute different nutritional and bioactive compounds, making various parts valuable for different applications. Understanding these distributions helps optimize harvests for specific uses whether culinary or medicinal.

The fruiting body contains concentrated beta-glucans, triterpenes, and other beneficial compounds that form during reproductive development. These substances accumulate as the mushroom prepares for spore production, creating the high nutritional value associated with harvested mushrooms. This concentration explains why mushroom fruiting bodies receive particular attention in both culinary and medicinal applications.

The cap typically contains the highest concentration of bioactive compounds since this structure houses the reproductive machinery and accumulates resources to support spore production. However, stems also contain valuable nutrients and shouldn't be discarded despite sometimes having tougher textures. Many cultivators save stems for stocks, extracts, or mushroom powder creation, utilizing the entire fruiting body rather than wasting any portion.

Mycelium also contains beneficial compounds, though often in different ratios than fruiting bodies. Some research suggests mycelium produces unique metabolites not found in fruiting bodies, while other compounds concentrate specifically during mushroom formation. This has led to ongoing debates in the medicinal mushroom industry about the relative values of mycelium versus fruiting body products. For home cultivators, both portions offer nutritional benefits when properly prepared.

Different mushroom species accumulate distinct compound profiles in their anatomical structures. Shiitake stems, for example, contain particularly high levels of certain immune-supporting polysaccharides, making them valuable despite their chewy texture. Lion's mane produces compounds associated with cognitive benefits throughout its cascading tooth structures. Understanding these distributions helps cultivators maximize the value of their harvests.

Common Questions About Mushroom Anatomy

What is the difference between mycelium and the mushroom?

The mycelium is the main body of the fungal organism—a vast network of thread-like hyphae that grows through substrate and absorbs nutrients. The mushroom (fruiting body) is a temporary reproductive structure the mycelium produces to create and disperse spores. Think of the relationship like an apple tree (mycelium) and its apples (mushrooms). The tree persists year-round while apples appear seasonally. Similarly, mycelium can live for years while individual mushrooms exist for just days or weeks. For cultivation, healthy mycelium visible as white growth throughout fruiting blocks indicates readiness to produce mushrooms when conditions become favorable.

Why do some mushrooms have gills while others have pores?

Gills and pores represent different evolutionary solutions to the same challenge—maximizing surface area for spore production within a compact fruiting body. Gilled mushrooms (Agarics) feature thin, blade-like structures that provide enormous surface area while remaining lightweight and resource-efficient. Polypore mushrooms develop pore structures that protect spore-producing tissue from environmental damage while still enabling spore release. Neither structure is inherently superior—each adaptation suits different ecological niches and dispersal strategies. Toothed mushrooms like lion's mane use yet another approach with hanging spines. These anatomical differences help mycologists classify and identify species while understanding evolutionary relationships between different fungal groups.

What does it mean when mushroom stems are hollow?

Hollow stems develop normally in many mushroom species as they mature. As the fruiting body ages and resources shift toward final spore production, the central stem tissue sometimes breaks down or was never densely packed initially. This anatomy is completely normal and doesn't indicate problems with growing conditions or mushroom quality. Species including oyster mushrooms, many Coprinus varieties, and certain Agaricus species regularly develop hollow stems. However, if mushrooms that typically have solid stems show hollowness, this might indicate inadequate nutrition during colonization or environmental stress during fruiting. Generally, hollow stems pose no food safety concerns and simply affect texture rather than flavor or nutritional content.

How do mushrooms grow so fast without visible roots?

Mushrooms achieve their remarkable growth rates through unique anatomy that differs fundamentally from plants. The mycelial network functions like roots for absorption but extends much more extensively than plant root systems. When conditions trigger fruiting, the mycelium has already accumulated substantial resources and constructed pre-formed cellular structures within tiny primordia. These compressed structures rapidly inflate with water pressure rather than building new cells from scratch like plants. This allows mushrooms to expand several inches in just 24 hours under optimal conditions. The process resembles inflating a balloon rather than constructing a building, explaining why mushrooms seem to appear overnight. Learn more about this fascinating phenomenon in our article on how mushrooms grow so fast.

Can you eat all parts of a mushroom including the stem and gills?

For cultivated edible mushroom species, all anatomical parts including stem, cap, and gills are safe to eat when properly cooked. However, different parts offer varying textures and flavors. Caps typically provide the most tender texture and concentrated flavor, while stems may be chewier but still nutritious and flavorful. Some species like shiitake have particularly tough stem bases that some cooks remove or save for stocks and broths. Gills are completely edible—in fact, they often contain the most concentrated flavors. The key consideration is species rather than anatomical part. Never consume wild mushrooms unless you've positively identified them as edible species, as toxic mushrooms look similar to edible varieties. With home-grown varieties from verified sources like Lykyn fruiting blocks, you can confidently enjoy all anatomical parts of your harvest.

Summary: Mastering Mushroom Anatomy for Growing Success

Understanding mushroom anatomy transforms cultivation from following instructions to truly comprehending your organisms' needs at each developmental stage. The visible fruiting body with its cap, gills or pores, stem, and specialized structures represents just the reproductive portion of a much larger organism. The hidden mycelial network of thread-like hyphae forms the true fungal body, absorbing nutrients and supporting fruiting when conditions become favorable. Each anatomical structure provides visual indicators of growing conditions—elongated stems signal poor air exchange, cracked caps indicate low humidity, and pale coloration suggests inadequate lighting. By observing and responding to these anatomical signals, cultivators optimize environments for healthy development and maximum yields.

Start Your Mushroom Growing Journey with Anatomical Understanding

Ready to apply your knowledge of mushroom anatomy to successful home cultivation? Understanding how mushrooms develop from microscopic hyphae through mature fruiting bodies helps you provide optimal conditions at every growth stage. Whether you're a beginner seeking foolproof success or an experienced cultivator wanting to optimize yields, proper anatomical knowledge forms the foundation of exceptional results.

Visit Lykyn's complete collection to explore the Smart Mushroom Grow Kit that automatically maintains perfect conditions for healthy anatomical development, plus ready-to-fruit mushroom blocks with fully colonized mycelium ready to produce beautiful mushrooms. Join thousands of home growers who've discovered that understanding mushroom anatomy makes cultivation more successful, more fascinating, and more rewarding.

For more growing guidance, explore our articles on mushroom grow bags, understanding the mushroom life cycle, and essential mushroom types. Your journey to mushroom growing mastery begins with understanding how these remarkable organisms are built!

Share:

The Complete Guide to Mushroom Bags: Everything You Need to Know About Growing Mushrooms in Bags